Drawing Capital Newsletter

February 9, 2021

Introduction

As a bonus edition for Drawing Capital’s weekly newsletter, we would like to discuss the current IPO landscape. For a review of Drawing Capital’s recent thoughts on the IPO and SPAC market, we are excited to share our recent webinar presentation at the following link:

Historical Context

We notice that the total number of publicly listed companies in America has declined from about 7500 in 1998 to 4400 in 2018. Possible reasons for this include:

M&A activity that consolidates multiple companies into one

Leveraged buyouts (LBOs) from the private equity industry

Extra costs and regulations to become a public company

Several private companies remaining private for longer periods of time

Some companies are going out of business

So the logical question we may ask is, why is this important? Well, when there is a constrained supply of public companies on the supply side and an increasing population that is seeking to buy stocks as the demand side combined with monetary debasement from continued expansionary monetary policy from central banks, basic supply and demand would suggest a natural price appreciation in the long term for stock market indices.

4 Common Methods of Going Public:

Traditional IPO

Direct Listing

Reverse Merger

Special Purpose Acquisition Company (“SPAC”)

As of today, there are four common methods for a company going public. The traditional IPO method has historically been the most popular method. In a direct listing, a company lists its private shares on a public stock exchange. In a reverse merger, a small publicly traded company merges with a private company to bring the private company into the public markets. In a SPAC-based transaction, a SPAC sponsor and a blank-check money vehicle take a private company public. SPAC stands for special purpose acquisition company, which raises money and trades on a stock exchange with a ticker symbol with the explicit purpose of merging with a private company in order to take the private company public.

Benefits of Being a Public Company

Interestingly, one may ask the question: What are the benefits of a company going public and having the company’s stock trade on a public stock exchange?

These 6 traits are the commonly cited reasons for a company going public:

Public markets can often facilitate larger fundraising efforts through an IPO and SPAC process compared to a private fundraising round from venture capitalists.

Going public also provides a marketing and branding opportunity for the company in attracting talented employees, having an established company presence in courting new enterprise customers, and celebrating the success of the founders and employees.

Going public provides a liquidity event for the company’s founders, employees, and early investors. When a company goes public, its stock also becomes a public currency, which allows the company to make share-based acquisitions and pay stock-based compensation (RSUs, stock options, performance-based stock grants, etc.) to employees in order to attract and retain talent.

A fourth reason to go public involves an increase in valuation. As we saw in 2020, many private companies, such as DoorDash, Snowflake, and Airbnb, saw significant price multiple expansion and a significantly higher market cap valuation compared to their previous fundraising round in private markets. Furthermore, because there is a constrained supply of enduring high-growth and high-quality companies in public markets and due to a low interest rate environment, investor demand for high-growth companies is exceptionally high. In addition, when a company goes public, the private shares no longer have an illiquidity discount, meaning that liquidity commands premium prices.

A fifth reason to go public involves investor diversity. When a company goes public, it increases the quality and diversity of both the company’s existing shareholder base and its prospective shareholder base. On the same token, investor scrutiny also increases from public market investors on public companies. Due to the restrictions surrounding investing in private companies, there are more buyers of stocks in public markets than in private markets.

A sixth reason to go public involves employee retention. For the majority of companies, having talented employees and a good culture is a key defining factor in the success of a company. Stock-based compensation can be a dual win-win scenario. The ability to use stock-based compensation to retain and attract employees is important, and stock-based compensation can be a key source of wealth generation for many employees.

3 Popular Benefits of Going Public via an IPO

The key benefit of an IPO is the ability for a company to fundraise for primary capital. Since the traditional IPO process has been accomplished thousands of times, it appears to have a “popular choice” phenomenon associated with going public as opposed to an experimental process. With the IPO process, the company has the ability to market IPO shares to investors and generate publicity. In addition, the company can direct shares to specific buy-side investors that hopefully align with the company’s long-term values and value-creation.

During the IPO process, the lead underwriting banks can also provide an initial price stabilization mechanism.

In addition, a supply-demand imbalance for IPO shares and IPO pricing uncertainty often lead to underpricing of IPO shares, which benefits buy-side investment firms and individuals that receive significant IPO share allocations at the IPO offering price.

Common Concerns of the Traditional IPO Process

On the flip side of IPO benefits remains concerns about the traditional IPO process. Namely, here are the seven popular concerns associated with the traditional IPO process:

Extensive IPO roadshow process

Uncertainty in company valuation, IPO opening price, and ownership dilution

Restrictions on providing future predictions and forecasts to investors and employees

Imbalanced pricing of IPO shares

Reduced access and limited participation of many retail investors and small institutional investors in buying IPO shares at the IPO offering price

Lock-up provisions for employees and pre-IPO investors

Multiple principal-agent problems with occasional conflicting interests between the company pursuing an IPO, underwriting investment banks, IPO investors, early investors, and employees

Notably, these critiques are not about IPOs but rather about the traditional IPO process.

First, there is an extensive IPO roadshow process in which the company’s management team frequently meets with investment bankers and buy-side investors. Despite all of these meetings, many investors often receive little guidance about a company’s future due to regulations that restrict a company’s ability to provide forward looking guidance and projections during an IPO process. Especially for high-growth innovative technology companies where the vast majority of a company’s value is based on the future as opposed to its past, this creates an interesting situation with uncertainty. This uncertainty is then quantified via often a lower-than-market equilibrium IPO offering price, which causes corporate fundraising inefficiency. Then, this inefficiency can be quantified as the IPO’s “money left on the table”, in which a company going public suffers from greater ownership dilution, meaning that the company could have either fundraised more money for the same percentage ownership or sold less of the company for the same fundraising amount.

Furthermore on the supply side, due to lock-up periods for pre-IPO equity owners, there is an artificially constrained supply, creating an imbalance between supply and demand that often orchestrates an IPO price increase on the day of the IPO. On the retail demand size, investment banks often place restrictions on the degree of participation for retail investors and give more IPO share allocation to large institutional investors in the IPO.

The IPO Underpricing Issue

IPO underpricing can be measured as the equally weighted average of the difference between the IPO offering price and the closing stock price on the day of the IPO. This underpricing is essentially a direct multi-billion dollar wealth transfer from the company’s balance sheet to specific equity shareholders (primarily the equity shareholders that were fortunate enough to have access to buy shares at the IPO offering price as opposed to the IPO’s opening price).

As shown from the data table above, the issue of net underpriced has steadily climbed over time. Based on the data from Professor Jay Ritter and assuming that the closing price on the day of the IPO reflects the willingness of public market investors to buy at that closing price, then IPO guidance from investment banks led to companies receiving an average of 41.6% less in IPO fundraising proceeds compared to what the market was willing to pay in 2020.

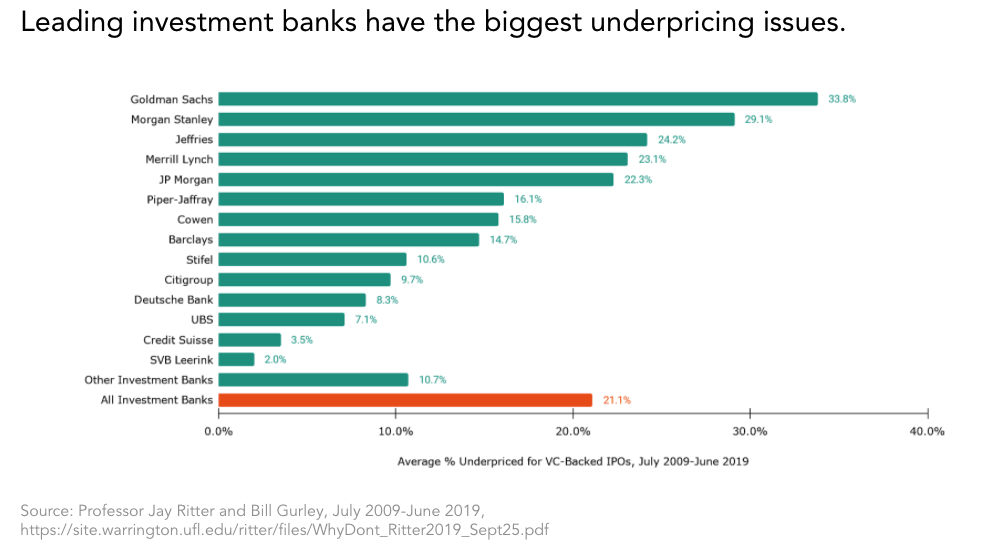

Interestingly, a couple of the most sought-after investment banks, such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, have the biggest IPO underpricing issues. The IPO shares underwritten at these investment banks are more underpriced compared to the average of the ~21% IPO underpricing across all major investment banks.

Diving deeper into the persistence of the IPO underpricing issue over time results in an interesting finding: There exists a dual principal-agent problem that creates a conflict between an investment bank’s corporate client (the company going public that desires a successful fundraising process, which can be a large yet limited-time revenue source for a company) versus an investment bank’s buy-side asset management clients (who desire to buy shares at cheaper prices and often provide repeat recurring business to investment banks).

Review of the IPO Landscape

Except for the 2019-2020 calendar years and the tech bubble in 1998-2000, the average first-day IPO percentage return has been in a steady range since 1978.

Companies like C3.ai, Airbnb, and Snowflake experienced an IPO first-day market closing price that was more than double the IPO offering price.

Another similarity between 2000 and 2020 is the annual gross proceeds from IPOs, suggesting that the IPO market is hot, and public market investors are willing to participate in IPOs to help private companies transition to become publicly traded enterprises.

In the last few years, the majority of biotech IPOs were for companies with immaterial revenue. An increase in the amount of pre-revenue biotech companies that went public via an IPO suggests that speculative capital exists among public market investors in order to finance early-stage biotech companies.

Interestingly, biotech company IPOs have a tendency to cluster around strong economic and industry-specific periods, largely due to economic expansion and the availability of excess capital from investors. In 2020, the number of biotech IPOs reached an annual record high between 1980-2020.

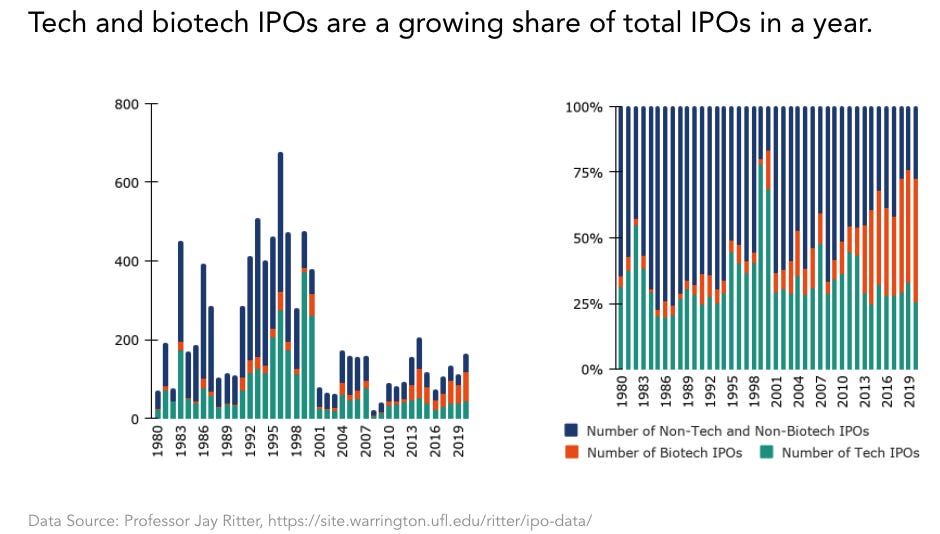

While the number of biotech IPOs reached all-time highs in 2020, the number of tech IPOs in 2020 remained relatively small compared to the exuberance displayed in 1995-2000.

LTM = last 12 months

While some investors may be concerned about another tech bubble today as a repeat of 2000, the data demonstrates that despite the recent upward surge in price multiples for IPOs in 2019-2020, these price multiples remain less than half of price-to-LTM-revenue multiples seen in 1999-2000.

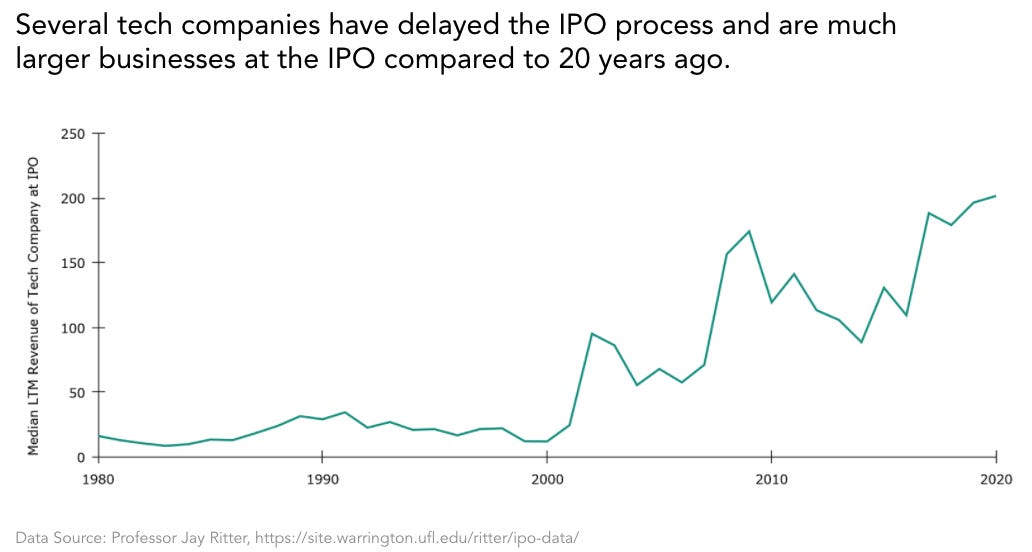

Compared to 20 years ago, many tech companies are delaying the process of going public, are willing to accept private financing rounds for several years, and desire to grow their revenues to a much higher level of sales traction before seeking to go public.

However, as a general trend, the profitability of tech companies in aggregate at the time of the IPO is significantly lower today compared to in 1980. The level of unprofitability in 2020 was near the level of unprofitability in the year 2000.

Looking at the LTM profitability of tech companies at the time of the IPO, a logical question can be asked: Within IPOs, what is a sample metric used to distinguish between money-losing companies with poor business models versus currently unprofitable companies that can eventually have a pathway towards sustainable growth and positive cash flows?

It’s a great question with lots of nuance. A key understanding of a business model is its unit economics. Many software companies have high fixed costs but very low variable costs, implying that after the initial fixed costs are overcome, the company has high operating leverage in its ability to generate future cash flows. When a company states that it is investing for growth, it’s important to understand if the company’s core business generates positive operating cash flows. Another metric to consider is a company’s contribution margin, which measures what percentage of revenue the company keeps after paying for variable expenses, such as cost of goods sold and sales and marketing expenses. Cost of goods sold, or COGS, shows the cost of producing a good or service, and sales and marketing costs on an income statement displays a company’s variable business development costs to acquire more revenue.

Technology and biotech companies are increasingly representing a growing share of total IPOs in a year.

Interestingly, biotech companies outpace tech companies on average in regards to speed to an IPO date from the company’s founding year. Recently, biotech companies have gone public in about half the number of years it takes a technology company to go public.

For context on how the historical IPO timelines compare to the timelines for “FANGMAN” companies to go public, we see that there was a wide dispersion for the length of time needed to go public. Among the “FANGMAN” companies, Amazon was the quickest to go public via an IPO.

Conclusion

The decision for a company to seek a public listing of its shares on a stock exchange represents an important milestone in a company’s journey. While the recent rise in direct listings and SPACs demonstrates the growing need for enhanced transparency, efficiency, prioritization of goals, and stakeholder management, IPOs remain a popular method for companies going public. Understanding IPOs and the IPO process can expand an investor’s knowledge and investing opportunity set.

Get in touch to learn more about Drawing Capital’s strategy:

References:

(1) Drawing Capital & Interactive Brokers. “Drawing Capital- IPOs and SPACs: The Next Evolution of Going Public”. 25 Jan 2021.

(2) Corporate press releases regarding company IPOs

(3) "Number of Listed Companies for United States ... - FRED." https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DDOM01USA644NWDB. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

(4) "Koyfin | Advanced graphing and analytical tools for investors." https://app.koyfin.com/. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

(5) "IPO Data - Jay R. Ritter - University of Florida." https://site.warrington.ufl.edu/ritter/ipo-data/. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

(6) "Why Don't Issuers Get Upset About Leaving Money on the ...." https://site.warrington.ufl.edu/ritter/files/WhyDont_Ritter2019_Sept25.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

This letter may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the express consent of Drawing Capital Group, LLC (“Drawing Capital”).

This letter is not an offer to sell securities of any investment fund or a solicitation of offers to buy any such securities. An investment in any strategy, including the strategy described herein, involves a high degree of risk. Past performance of these strategies is not necessarily indicative of future results. There is the possibility of loss and all investment involves risk including the loss of principal.

The information in this letter was prepared by Drawing Capital and is believed by the Drawing Capital to be reliable and has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. Drawing Capital makes no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of such information. Opinions, estimates and projections in this letter constitute the current judgment of Drawing Capital and are subject to change without notice.

Any projections, forecasts and estimates contained in this document are necessarily speculative in nature and are based upon certain assumptions. In addition, matters they describe are subject to known (and unknown) risks, uncertainties and other unpredictable factors, many of which are beyond Drawing Capital’s control. No representations or warranties are made as to the accuracy of such forward-looking statements. It can be expected that some or all of such forward-looking assumptions will not materialize or will vary significantly from actual results. Drawing Capital has no obligation to update, modify or amend this letter or to otherwise notify a reader thereof in the event that any matter stated herein, or any opinion, projection, forecast or estimate set forth herein, changes or subsequently becomes inaccurate.